India’s Strategic Loneliness in the Age of Trump; Remembering India's Political Prisoners at the Start of 2026

A newsletter from The Wire | Founded by Sidharth Bhatia, Siddharth Varadarajan, Sushant Singh, Seema Chishti, MK Venu, Pratik Kanjilal and Tanweer Alam | Contributing writer: Kalrav Joshi, with additional inputs by Anirudh SK

Won’t you please start the New Year by becoming a paying subscriber to The India Cable?

If you like our work and want to support us, then do subscribe. Sign up with your email address by clicking on this link and choose the FREE subscription plan. Do not choose the paid options on that page because Stripe – the payment gateway for Substack, which hosts The India Cable – does not process payments for Indian nonprofits.Our newsletter is paywalled but once a week we lift the paywall so newcomers can sample our content. To take out a fresh paid subscription or to renew your existing monthly or annual subscription, please click on the special payment page we have created – https://rzp.io/rzp/the-india-cable.The ruling establishment is playing down the significance of New Year’s Day by emphasising its foreign origins:

[Translation: “Friends, today is January 1. I want to congratulate you all that on the name of the Roman god Janus, originally propagated by the Roman king Numa Pompilius, started by Julius Caesar, corrected in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII, and adopted by the British in 1752 — hearty greetings on the first day of this English New Year.”]

Of course, we aren’t fully convinced, so we are going to celebrate anyway, by taking the day off. Kinda. By giving you just a Long Cable, but an important and significant one, we believe.

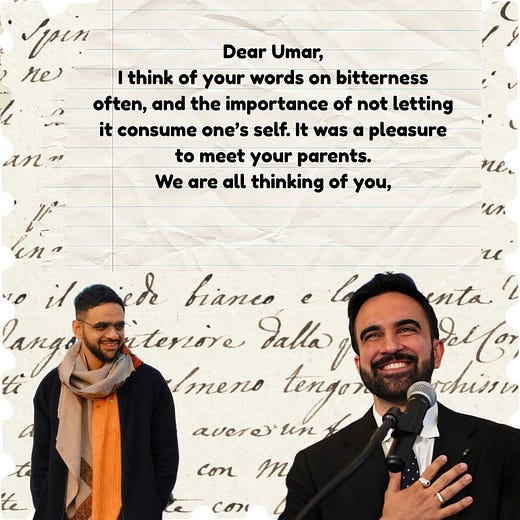

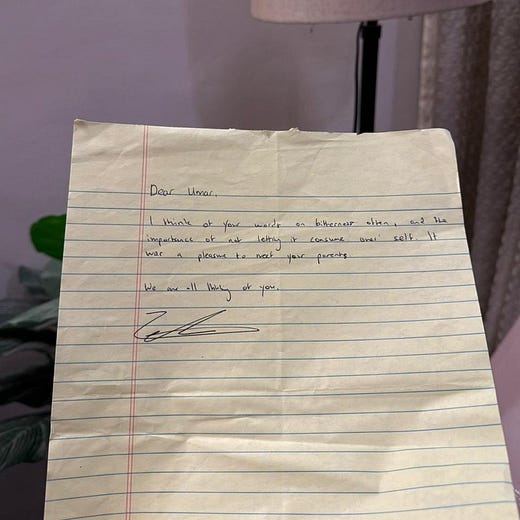

PS: What would a new year be without resolutions so here’s one: India should resolve to free its political prisoners. Beginning with its most iconic one, Umar Khalid, already in jail for five years without trial. He was given two weeks interim bail at the end of December to attend his sister’s wedding but is now back in Tihar.

PPS: Here’s New York mayor Zohran Mamdani’s note to Umar.

The Long Cable

India’s Strategic Loneliness in the Age of Trump: Why It Needs a Nehru Now

Sushil Aaron

The Indian state and Indian people have had a good run in the Western world over the last 25 years. The West recognised India’s potential as a big market for its goods, services and weapons. India was seen as having a role in its effort to balance the rise of China. President George W Bush drove the effort to bring India to the high table of international affairs through the Indo-US nuclear deal. Indians, meanwhile, took advantage of globalisation and emigrated in millions to the West, as students and working professionals. Indian doctors and IT engineers became emblematic of the community’s success abroad; Indian film, food and culture secured a share of the spotlight too.

Donald Trump is, within a year of his second Presidency, effectively threatening to overturn all that. His administration has imposed 50% tariffs on Indian goods, owing to Delhi’s continuing import of Russian oil. Strong words have ensued from the Americans. US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent accused India of profiteering over Russian oil. Trump continues to call Prime Minister Narendra Modi his “good friend” but keeps bringing up, to India’s dismay, the claim that he brought the India-Pakistan hostilities to an end in May. Things have come to such a head that PM Modi gave the ASEAN Summit an entire miss, probably to avoid an awkward public exchange with Trump.

The crisis of Indian elites

More worrying for average Indians is the growing disaffection for them in the Western world. Trump’s allies in Silicon Valley may want more Indians working in their tech companies but his MAGA base is firmly against more immigration. Steve Bannon, a former Trump adviser and influential MAGA figure, wants an end to H-1B visas. Indians have been viciously targeted in online MAGA spaces in recent months; videos alleging their violation of civic norms have circulated widely. Prominent Christian figures have jumped in as well; tagging images of Hindu festivals as proof that American culture is changing. FBI Director Kash Patel was relentlessly trolled for a tweet on Diwali observance in the White House. Trump’s open criticism of India seems to have provided MAGA the permission structure to freely air their prejudice against Indians.

This trend is unlikely to change. Anti-immigration is now a key feature of the West’s political evolution and the cultural climate for welcoming Indians is unlikely to get better.

In historical terms, the implications are fairly clear: The closing of borders in the West constitutes the greatest challenge that Indian middle classes and elites have faced in their pursuit of prosperity in recent decades.

In independent India, educated Indians took to the civil service, medicine, engineering and armed forces to get ahead. Since the liberalisation of the Indian economy in the 1990s, Indian elites have switched from aspiring to public sector employment to becoming part of the globalized mix of IT workers, doctors and entrepreneurs. Millions have headed abroad in recent decades to study and settle elsewhere. It is not too much of a stretch to say that India’s elite reproduces itself abroad in significant measure – and it is this trend that Trump, MAGA (and conservatives in Europe) are threatening to overturn.

Troubles elsewhere

The problem for India is that the West is not the only front that it is having trouble with. Things are not going well in the South Asian neighbourhood as well. Ties with Pakistan remain fraught as ever. Bangladesh and Nepal are drawing closer to China. Sri Lanka and Maldives have long had constituencies hostile to Delhi.

Further afield, India has good ties with states in the Persian Gulf, but people in the Muslim world at large – stretching from Turkey in the west to Indonesia in the east are unlikely to be unaware of the illiberal, anti-Muslim rhetoric of the ruling BJP. Likewise, Moscow may appreciate India’s purchase of Russian oil but would not forget how enthusiastically India embraced the West over the last 25 years. China may now be keen on resuming economic ties to counteract the effects of Trump but it is unlikely to accord India the equal status the latter craves or enable the kind of technology transfer that the US allows.

Adrift from the US, relatively friendless in the neighbourhood, frowned on by Muslim-majority populations, and its diaspora unwanted by anti-immigrant conservatives everywhere, India now finds itself unable to point to any power, possibly barring Russia, as an all-weather friend. There isn’t a region that it can claim to significantly influence. It is in this broad sense that India is currently experiencing strategic loneliness.

Recognise certain realities

Where do Indian policymakers go from here? They could start by investigating how this situation came to be and recognixe certain realities as they think through a response to current challenges.

They could first note that a liberal, rules-based order worked mostly to India’s benefit, and is preferable to one dominated by strongmen and purely transactional amoral tactics. This is important to keep in mind as India gears its grand strategy towards the order that it wants to see restored. Only in a rules-based order would other nations call for India to become a permanent member of UN Security Council on the grounds of equity. Only a liberal order would allow India to rhetorically challenge other powers in terms of the norms and principles that they have all agreed to.

By extension, Indian leaders could register that realism is not always a rewarding approach in international affairs. Indian analysts and policymakers have tended to fetishize realism as a guiding principle to manage foreign affairs, speaking only in the language of interest, framing it narrowly, privileging dealmaking and considering values as irrelevant. But that value in itself doesn’t work if every nation adopts it: no one really likes it when the US embraces hard-nosed realism at the expense of principle. If every power cynically thinks of looking out for its own, what becomes of the common good – and what place would there be for small and middle powers in the world order?

India thus needs to recognise that populist far-right ideology and Trumpism, with their ethnonationalist objectives, are not the answers to the challenges of the age.

Instead, what India needs is to find a way for the world to listen to it, and the primary way to do so is to articulate intellectual and moral positions that have explanatory appeal and emotional resonance – in ways that India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru managed to do in the past.

Nehru was the leader of a poor, newly-independent country but was able to speak imaginatively to great powers as they were fashioning a transformed postwar order. He spoke out against imperialism, supported national liberation movements, and created a space for the politics of non-alignment to steer clear of polarising power blocs. He practiced the politics of value affirmation to fashion a leadership identity for India; he demonstrated that it was possible to use idealist rhetoric to compensate for his country’s material deficits – he strived to articulate a vision for the world that allowed third world countries to express themselves while also economically developing.

India is lacking that leadership quality now and no longer takes a principled or striking stance on issues that the world thinks about, be it Ukraine, Gaza, economic inequality, immigration, open borders, climate change etc. It seems to operate with the belief that foreign policy is about dealmaking among political and business elites alone. That may well be the case when global orders are more or less settled, but that approach doesn’t work when systemic change is in progress, when US hegemony is ending and when strongmen are stepping into the interregnum, before a new order emerges.

It is, in fact, in times of such political flux that there is hunger for values and a vision, to go beyond the extractive instrumentalities of the present.

These interventions would, in due course, entail talk of values, human rights and democracy to carry any force and purchase. And while some would suggest that the call for justice and fairness have no place in an international system marked by anarchy, it is the case that even strongmen use the language of principle to justify their policies. Trump speaks about fairness in the context of tariffs and equity when making the case for more defence spending from NATO allies. International affairs can thus never be entirely drained of moral language, however much realists and statesmen prefer to deal in the idiom of coldly-calculated interest.

In other words, there is always a market gap for a country or a leader to speak forcefully to a world in crisis. One of the reasons India is unable to do so is because there’s the absence of a connective tissue between the values it espouses abroad and those it practices at home. Indian leaders extol democracy and the rule of law to foreign audiences while stoking illiberalism towards minorities at home and this is undermining the country’s appeal abroad.

Bring back the template

This was not the case in the past. The world was never in doubt that Nehru was a liberal at home, he protected minority rights for the most part, he was generous to political adversaries, was committed to democratic deliberation, scientific temper and rationality, and had a firm view on the direction of international affairs. Nehru curated a persona for India to adopt, which helped to fortify the liberal dimensions of world order. The country has since strayed from the template he provided and is today marked by none of the qualities that gave it stature in the past, especially the openness to diversity and the instinct to stand for principle. The disjunct between India’s claims abroad and the realities at home are preventing Delhi from espousing a vision that other nations can rally to. How a country addresses social cohesion at home determines to an extent what it is able to say abroad.

This disconnect has real world implications in terms of perceptions abroad as India is not seen as truly being on anyone’s side: western democracies are liable to view India as an “electoral autocracy”, while authoritarian countries like Russia and China see India as a wannabe democracy whose fundamental sympathies lie with the West. India’s loneliness is further compounded by shifting affections to China in the subcontinent and the views of Muslim-majority nations in Asia about treatment of minorities in India.

This is not a situation that India would want to be in as an aspiring Vishwaguru, or world leader.

To reverse these trends Indian leaders could, as noted, begin by recognizing and affirming that it is the liberal, rules-based order that needs to be restored or strengthened – and do the best to align domestic politics in ways that support that order. India cannot ask for open borders for its students and professionals abroad while being discriminatory and averse to cultural diversity at home. If India expects the United States and European countries to be true liberal democracies, so that the interests of its diaspora are advanced, then it better be one itself.

Some may contend that India wouldn’t need moral contortions in foreign affairs if it focused on building up its national power and economy at home. Focusing on power is certainly important, but values matter in how they are applied in this sphere too. For instance, India’s recent economic path has been marked by high levels of inequality with the state orchestrating a transfer of wealth to a few conglomerates, rather than choosing to spread prosperity and opportunity more widely across society. India’s fracturing of society along communal lines is also a severe constraint on economic prosperity. Only a resolute commitment to equal opportunity and provision of social space for collaboration can unlock the potential of India’s millions.

Twin responsibilities

India’s government and its people have responsibilities ahead of them as they confront the uncertainties of the populist age. The state needs to offer a consistent and full-throated backing of the international order and re-institute a measure of democracy in its domestic politics and economy, which would give such backing the requisite force and authority abroad.

Meanwhile, Indians living and settling abroad need to decide what form of politics they will pursue in other countries, as the West goes through its own democratic struggles.

The diaspora has two choices before it. One is to persist with BJP’s ethnonationalist instincts to align with other right-wing movements abroad in confronting the Left, in an effort to consolidate majoritarian politics in India. That is no longer a viable option given the MAGA’s outlook toward Indians, alongside those of far-right forces in Europe and Australia.

The other path is to get behind left-liberal movements and constituencies in an effort to sustain the globalization that worked well for Indians. But that effort has to have a measure of integrity sewn into it: endorsing majoritarianism in India does not square with practicing liberal politics elsewhere. Such hypocrisy gets found out pretty quickly in the glare of social media.

Indians have a readymade model to emulate in New York city mayor Zohran Mamdani, who has mobilized many ethnicities through his progressive politics, unapologetically embracing both cultural difference and egalitarian outcomes. He demonstrated the power of articulating values openly, to the extent that even Trump recognized the public mood behind him and hosted him in the White House.

It is not for nothing that Mamdani invoked Nehru’s famous speech in his victory address: “A moment comes, but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

An age has ended. The world waits for India to find utterance, as Trump’s depredation of the liberal order continues.

Sushil Aaron writes on politics and foreign affairs. He posts on Bluesky and X: @SushilAaron.